The word protein is derived from Greek word proteos which means "primary" or "to take place first." It is the nitrogen-containing part of food that is critical to life as it is involved is a wide array of roles within the human body such as being structural components, contractile filaments for muscle (actin-myosin), antibodies for our immune systems, transport vehicles in the blood such as those for iron (transferrin), hormones, enzymes, and more. Proteins are composed of amino acids, and only 20 amino acids are genetically coded from mRNA. Out of these 20, humans are unable to synthesize eight amino acids therefore we must consume them via dietary proteins, termed essential amino acids. Depending on the conditions in the body some of the non-essential amino acids (meaning those that our body can make) can become essential amino acids.

The net rate of protein synthesis and degradation is collectively known as protein turnover. The maintenance of muscle mass in the body is a balance between protein synthesis and muscle protein breakdown. As endurance athletes we want to maximize this balance in favor of synthesis and this is done by exercise and protein ingestion. The processes behind the adaptations such as translation, gene transcription, etc., are too complex and not necessary to the purpose of the post. While a lot of papers focus on positive protein balance being beneficial to resistance trained athletes, it is reasonable to speculate that a positive protein balance would also aid endurance athletes by increasing mitochondrial protein synthesis/volume (which is the cell organelle responsible for aerobic respiration, hence more mitochondria higher VO2 max, better performance). One study has shown that post-endurance exercise supplementation with protein resulted in greater improvements in peak oxygen uptake

The net rate of protein synthesis and degradation is collectively known as protein turnover. The maintenance of muscle mass in the body is a balance between protein synthesis and muscle protein breakdown. As endurance athletes we want to maximize this balance in favor of synthesis and this is done by exercise and protein ingestion. The processes behind the adaptations such as translation, gene transcription, etc., are too complex and not necessary to the purpose of the post. While a lot of papers focus on positive protein balance being beneficial to resistance trained athletes, it is reasonable to speculate that a positive protein balance would also aid endurance athletes by increasing mitochondrial protein synthesis/volume (which is the cell organelle responsible for aerobic respiration, hence more mitochondria higher VO2 max, better performance). One study has shown that post-endurance exercise supplementation with protein resulted in greater improvements in peak oxygen uptake compared to carbohydrate supplementation post-exercise. Basically if protein supply is in close

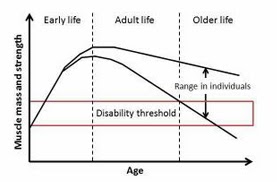

proximity to endurance exercise better adaptation, better subsequent performance. However, having said that, an overwhelming gap is apparent in the research regarding protein supplementation and endurance athletes, research is heavily focused on the resistance athlete. Although, one could argue that understanding resistance exercise is more vital than aerobic exercise due to it being especially important to our aging population (baby-boom cohort) to help fend off sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass), and maintain muscle coordination to avoid falls. So basically I understand why the research is so slanted towards resistance exercise.

Now to the real information about how much protein to consume post-exercise, when to consume it, and what type. I will start which the amount. According to the US Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) individuals over the age of 19 should aim to consume 0.8 g of protein/kg body weight per day. Living in North America, most of our diets exceed this value astronomically due to the high intake of meat. Some figures show that in the North America individuals consume about double the DRI. For reference, a 8 oz. sirloin steak has approximately 60 grams of protein, a small (3.5 oz.) chicken breast has 30 g, and a 5 oz salmon fillet has about 45 g. So just imagine, if you consume a piece of steak for dinner, assuming your around 150 lbs, you have already surpassed your protein requirements for the day. Having said all that, athletes need a greater amount of protein to facilitate the volume of training. A number of studies such as Tarnopolsky et al. (1993) from McMaster University cite that endurance athletes need to consume more protein than 0.8 g/kg BW to supplement the increased amount of leucine oxidation that occurs during exercise. The data varies on the optimal amount but most suggestions falls between athletes consuming 1.2-1.4 g/kg BW per day. In terms of how much athletes should look to consume following a bout of exercise to maximize muscle protein synthesis, a protein dose-response relationship was shown to exist by Moore et al. 2009 (who is at UofT and presented his research to my nutrition aids class). In the study, the authors showed that muscle protein synthesis increased as protein was increased from 0-20 g following a bout of exercise, however, when the athletes consumed 40 g there was no increase. This indicates that at these high protein intakes the excess amino acids were oxidized. So the consensus is that around following a exercise bout athletes should try to consume 20-25 g of high-quality protein.

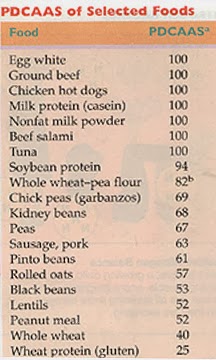

Now to the real information about how much protein to consume post-exercise, when to consume it, and what type. I will start which the amount. According to the US Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) individuals over the age of 19 should aim to consume 0.8 g of protein/kg body weight per day. Living in North America, most of our diets exceed this value astronomically due to the high intake of meat. Some figures show that in the North America individuals consume about double the DRI. For reference, a 8 oz. sirloin steak has approximately 60 grams of protein, a small (3.5 oz.) chicken breast has 30 g, and a 5 oz salmon fillet has about 45 g. So just imagine, if you consume a piece of steak for dinner, assuming your around 150 lbs, you have already surpassed your protein requirements for the day. Having said all that, athletes need a greater amount of protein to facilitate the volume of training. A number of studies such as Tarnopolsky et al. (1993) from McMaster University cite that endurance athletes need to consume more protein than 0.8 g/kg BW to supplement the increased amount of leucine oxidation that occurs during exercise. The data varies on the optimal amount but most suggestions falls between athletes consuming 1.2-1.4 g/kg BW per day. In terms of how much athletes should look to consume following a bout of exercise to maximize muscle protein synthesis, a protein dose-response relationship was shown to exist by Moore et al. 2009 (who is at UofT and presented his research to my nutrition aids class). In the study, the authors showed that muscle protein synthesis increased as protein was increased from 0-20 g following a bout of exercise, however, when the athletes consumed 40 g there was no increase. This indicates that at these high protein intakes the excess amino acids were oxidized. So the consensus is that around following a exercise bout athletes should try to consume 20-25 g of high-quality protein.What do I mean by high-quality protein? As you probably already know there are a number of different sources we can get protein from our diets. For example, we get protein from animal sources like milk (casein and whey), eggs, meat, plant sources like soy, etc. Such protein sources are graded on the

"Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score" which evaluates a protein's quality based on the amino acid requirements and our ability to digest the protein (ranges 0-1). For example wheat protein (gluten) achieves a score of only 0.25. Why? Well because it lacks a couple amino acids, and it is not as digestible. This is why vegetarians need to combine plant protein foods that have different complementary amino acids to yield a complete protein (or just have quinoa since it is a complete protein). In comparison, animal proteins such as eggs, milk, and meat score a perfect 1.0 of the scale meaning they are very high quality proteins. Soy protein is also a very high quality protein. So after a run or workout you want to look to consume 20-25g of milk protein (whey/casein) or soy protein. Just for reference straight up milk is about 80% casein protein and 20% whey. Having said this, these three proteins (casein, whey, and soy) differ in there digestion rate. Casein for example clots in the stomach and is very slowly digested, compared to whey protein which is rapidly digested (soy is somewhere in the middle). So for an endurance athlete in terms of which source to consume after a workout, I would say that largely depends on the workout schedule for the day. For example, if your doing a double workout soon after the first, I wouldn't recommend having lots a casein protein as that may cause some GI problems during the second workout since it takes so long to digest. In that case, whey protein would be the best. However, if you are running late at night, maybe something high in casein would be better since your muscles can "munch" on that casein protein all night long. Overall, most studies have shown milk protein is superior to soy protein.

"Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score" which evaluates a protein's quality based on the amino acid requirements and our ability to digest the protein (ranges 0-1). For example wheat protein (gluten) achieves a score of only 0.25. Why? Well because it lacks a couple amino acids, and it is not as digestible. This is why vegetarians need to combine plant protein foods that have different complementary amino acids to yield a complete protein (or just have quinoa since it is a complete protein). In comparison, animal proteins such as eggs, milk, and meat score a perfect 1.0 of the scale meaning they are very high quality proteins. Soy protein is also a very high quality protein. So after a run or workout you want to look to consume 20-25g of milk protein (whey/casein) or soy protein. Just for reference straight up milk is about 80% casein protein and 20% whey. Having said this, these three proteins (casein, whey, and soy) differ in there digestion rate. Casein for example clots in the stomach and is very slowly digested, compared to whey protein which is rapidly digested (soy is somewhere in the middle). So for an endurance athlete in terms of which source to consume after a workout, I would say that largely depends on the workout schedule for the day. For example, if your doing a double workout soon after the first, I wouldn't recommend having lots a casein protein as that may cause some GI problems during the second workout since it takes so long to digest. In that case, whey protein would be the best. However, if you are running late at night, maybe something high in casein would be better since your muscles can "munch" on that casein protein all night long. Overall, most studies have shown milk protein is superior to soy protein.This flows nicely into my next point on the timing of protein consumption. Often you hear athletes in the gym say they need to quickly get home, or to the store to buy some chocolate milk right away since they believe firmly in something called the "anabolic window." Many people believe that if they don't get there protein shake within a certain time limit (an hour) after the workout than the whole workout is wasted. Even in commercials such as the chocolate milk one, recommend you consume the product within 20 minutes of working out. Well, the fact is this is not backed by any reliable scientific research. In fact just one example of many, Reasmussen et al. found there was no significant difference in leg net amino acid balance when whey protein was ingested 1 versus 3 hours post-exercise. So don't worry about having to shower and stretch as quickly as possible to get in your protein, your muscles are not going to fall apart.

To put everything together, you've finished a 2 hour run and your done your exercise for the day. What do you do? Consume 20-25g of high quality (milk or soy, preferably milk protein) sometime after the run, and don't worry if it's a couple hours afterwards. Seems simple right...But I will throw in a caveat to that. If you are a endurance athlete consuming more 3, 4, or 5000 calories a day, do you really need to go buy a jar of whey protein isolate. Probably not. The fact is based on the number of calories you are putting in everyday you are most likely already getting 1.2-1.4 g of protein/kg of body weight per day. So the simple way to get in your 20-25 g post-workout is just to consume that through you post workout mixed meal, and not necessarily an expensive protein rich shake - and absolutely not Booster Juice, the biggest waste of money ever. Also, you could just have some skim milk after the workout - lots of protein plus lactose sugar which will help replenish glycogen stores if that workout was longer than 2 hours. Overall, the fact is that if you are consuming the typical North American diet, high in

|

| I think this graph from study of UofWashington is pretty amazing. As Canadians we consume 94.3 kg of meat per person per year - that is over 200 lbs. |

One last thing, just for fun (maybe I'm the only one who thinks its fun/interesting) track how much protein you are consuming per day and correct it to your body weight (g of protein/body weight in kilograms). I bet most of you would be shocked to see how much protein you are actually already getting. Make sure you take into account all the protein you are eating not just the protein from the steak at dinner. For example, if in the morning you put a couple of Tbsp of peanut butter on toast, that is 6g of protein plus about 8 g from the toast (14g total). Overall, become more conscious of what you are eating, and look for areas you can improve. Because if you eat right your body will repay you with high performance. In other words, Fuel the fire.

References

Phillips SM, Van Loon LJ. Dietary Protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. JSS 2011; 29: S29-S38.

Stark M, Lukaszuk J, Prawitz A, Salacinski A. Protein timing and its effects on muscular hypertrophy and strength in individuals engaged in weight training. JISSN 2012;9:54